Experiencing Love

written for Professor Anna Russakoff for Ancient Art and Architecture, a class at the American University of Paris, Spring 2020

“Love is a many splendored thing,” wrote Victorian mystic Francis Thomas.[1] The facets of love are varied and complex, as Thompson observed. Many artistic images try to capture the splendor of love: beautiful women, beating hearts, and images of intimacy and tenderness all try to communicate feelings of love. Thompson in the Victorian age conveyed era-specific concepts, yet even in the ancient world, the “many-splendored” facets of love were present. The ability to harness and play with concepts such as emotion, symbolism and even voyeurism through art are skills demonstrated repeatedly in art of the eras before Christ. Love has always been an integral part of who we are as human beings, it is a question we still experiment with in art and an experience that appears in many different forms. Ancient art comes from people not all that different from ourselves and reflects many ideas on how to express or capture love in forms often purer than we may find today.

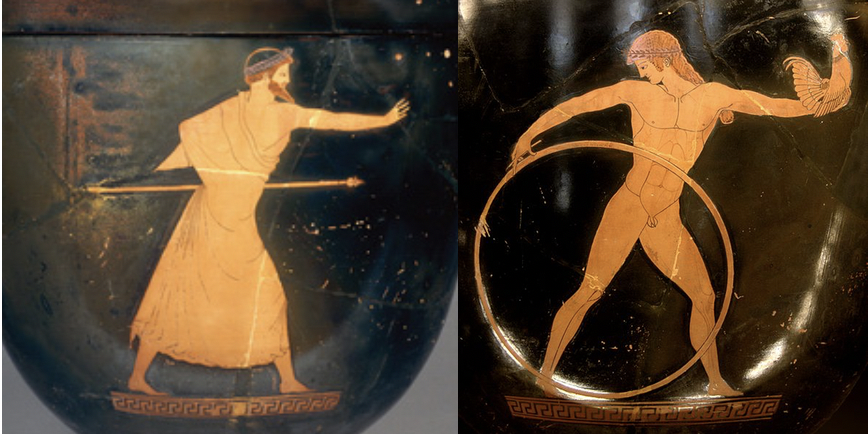

Mycenaean art was not known for its poetry or romanticism through art; they decorated their lives with scenes of harvests or soldiers, with animals and more simple, spiraling design. The love that they have captured in their art is often from everyday life, tender but practical moments. In Mycenaean art, the love we see depicted is more implied than anything else. It does not declare itself overtly. One example of this subtle portrayal is a small Mycenaean terracotta clay figurine of a woman and child, found in the Louvre’s collection (Figure 1). The woman sits in a chair, her body leaning back and becoming a part of it. The figurine is painted with simple lines and patterns that accent the chair, the woman’s face, body, and child. The baby sits in the crook of her arm, so small it almost blends in completely with the female body and yet we know almost instinctively that the child is there with her because of the wide, cradling curve of her arms.

Our common humanity is simply conveyed in this piece, for anyone would recognize a woman cradling a child. The child’s head is tipped up as if waiting for the breast above them that is just out of reach. We can easily infer that this is most likely a depiction of a mother and child. Unlike some other categories within the realm of love, parental love is universally understood. The ancient Greek language conveyed this type of familial love with the unique word “Storge” (στοργή) to distinguish this type of love from more erotic or passionate types of affection.[2] The intimacy of this image, woman cradling child, is one that we do not find in a lot of other Mycenaean art, as Olsen mentions in her paper on women, children and family in Minoan and Mycenaean art. She writes about the Mycenaean period, “Images of women and children are absent from Mycenaean frescoes, glyptic, pictorial painted pottery and metalwork (…) The corpus of kourotrophoi consists of approximately seventy terracottas, a small but significant subset”[3] So, these figurines of woman and children have appeared enough to merit their own name of ‘kourotrophoi’, which comes from the Greek for ‘child-nurturer’.

Nurturer is an emotional term: to nurture you must care, you must be committed. To nurture successfully there is always a loving emotion involved. Along with the nurturing emotion it suggests the kourotrophoi may also symbolize fertility, which can be another aspect of love. To be fertile is to be desirable. Desire emerges out of attraction and attraction is a definite component of other categories of love. The Mycenaean artist captured the simplicity of “Storge” style love – that found through familial intimacy, not with a goddess or a sexual innuendo as we see in later Greek art. Although this is a simple piece and a small one, it still captures a true hint of emotion and begins to chip away at the stiffness that can often pervade the ancient art preceding and accompanying the Mycenaeans, and leads naturally to other expressions of love. After all, Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of love, is not only a goddess of love and beauty but of fertility as well.

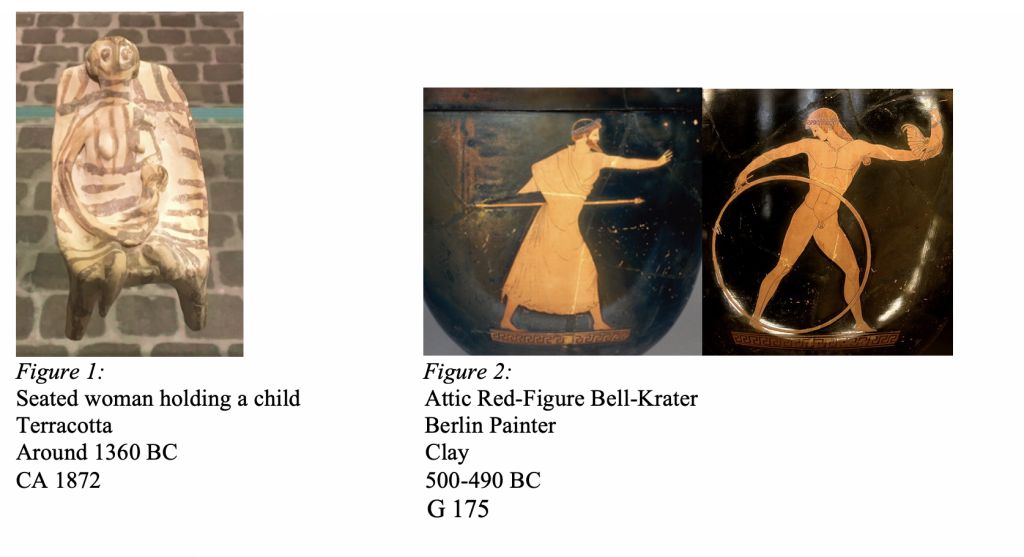

In contrast, Classical Greek art took quite a different turn from the earlier Mycenaeans and did not shy away from a very different side of love. This period of art did not shy away from the more sexual expressions of love. These art forms move from the Greek idea of “Storge” to the idea of “Eros” (ἔρως) , where our word “erotic” is derived.[4] This is clear to see from the Attic Red-Figure Bell-Krater decorated with Zeus and Ganymede (Figure 2). On this bell-krater the Berlin painter has put Zeus on one side and Ganymede on the other, depicting them through beautiful red-figure style. Zeus holds a spear, aiming it around the curved side of the vase towards Ganymede on the other side. The young Ganymede is playing with a hoop while his other arm is outstretched, allowing a rooster to perch there. It is not clear exactly why the rooster has been chosen but we can think first of the fact that roosters crow at dawn are so in a certain capacity they bring the sun. Zeus is considered the god of the sky and heavens so there may be a connotation there between the bird and the god. There is also a paper by John Boardman which explores the idea of the phallic bird and its symbolism throughout a lot of both archaic and classical art. As Boardman states “in the Late Archaic period and for a while later it appears to be used by artists in a very special way and to express a very special attitude”[5]. The long and stiffly upright neck of the bird that Ganymede is holding may certainly fall into this category of the suggestive, phallic bird, creating yet another opportunity for sexual innuendo in this piece. Even in the modern era, our slang word “cock” for male genitalia is a reference to a rooster. Roosters also crow at dawn, so in a certain capacity they bring the sun. Zeus is considered the god of the sky and heavens so this connection between fertility and godhood is present in the symbolism of the bird and the god.

In the mythology Zeus is overcome by the beauty of the young Ganymede and abducts him. This story is not exactly the overt narrative that the bell-krater is depicting for its viewers but the story instead exists more in the realm of pure suggestion. All the bell-krater gives us is the symbolism, and the story itself is left as an exercise for the viewer. There are hints to the story: the two props that Zeus and Ganymede carry represent the two sexes. One, the spear that Zeus holds, is clearly phallic while the other, Ganymede’s hoop, a decidedly feminine shape. The artist has reduced this scene to its most important motivation of sexual attraction. Here we see a clear dive into symbolism and no thought to shy away from the sexual side of “Eros” love. As viewers unpack this story, we once again are embraced by that most well-known and respected symbol for love: Aphrodite.

When the Greeks and Romans thought of love they thought of a goddess, of Aphrodite (known as Venus to the Romans). Aphrodite represented all the many-splendored aspects of love for the Greeks, from agápe, to éros, from philía, to storgē. Beauty, pleasure and fertility were all Aphrodite’s domains. By the end of the 4th century Aphrodite exists as the clearest indication to what sort of relationship the people of the time had with the concept of love; for them love and sexual desire were deeply connected. While there are other gods, such as the three graces who also represent fertility and beauty, it is only Aphrodite who is given the role of love. She is love’s purest marker along with the Cupid. Yet Cupid is also the son of Aphrodite, so in every sense of the word, she is love’s mother. Cupid represents a more nuanced version of love as well, he stands purely for the attraction found in sexual desire. The fact that all of these aspects of love derive from Aphrodite makes clear just how overlapping sex and love became for the ancient Greek people.

In Vénus Anadyomène, we see a further exploration of the power of Aphrodite in Greek culture. Vénus Anadyomène is a piece from the late 4th century or early 5th century and depicts the goddess of love freshly risen from the sea (Figure 3). Surrounding this Venus are three childlike figures, most likely angels, gathered around her feet, one even rides a dolphin. The dolphin serves as one of the only concrete indications that Venus is rising from the ocean, as the artist did not actually create any waves beneath her. She is holding something in her left hand that appears like a scepter or a decorated handle. As Venus is the goddess of beauty this could possibly be the handle of a mirror; she seems to stare longingly just above the top of this piece she holds up, giving the illusion that she could be staring at her reflection. Her right hand is preoccupied with her flowing hair that she grasps just above her shoulder, as if about to wring the wetness of the sea out of it.

Although Vénus Anadyomène is not an explicitly sexual piece, this image of Venus’s birth and emergence from the water communicates a strikingly evident sexual connotation. After all, we know that Venus was born from sea foam and Uranus’s severed genitals, thrown into the ocean after they are cut off by his son Cronos.[6] There is obvious symbolism here purely within the fact that the beautiful woman who becomes the goddess of love is born from a man’s sexual organs. This specific portrayal of Venus as she is born, later given the name Venus Anadyomene, becomes quite famous throughout different points in history. We think immediately of Botticelli’s famous painting Birth of Venus, and there are countless other works throughout art history that adopt this same vision. Heckscher writes about the anadyomene in his text which primarily explores Medieval art and not ancient art. Yet Heckscher’s observations are applicable here. He states: “An analogous chain can be established for the pose of the Anadyomene (…) its implications – vulgar as well as sublime – were never quite forgotten or lost sight of.”[7] The fact that this is the sight and story from which we can always identify Venus speaks volumes for the kind of love that dominated the art of the 4th century as well the effect that this early mythology had throughout all of art history. “Vulgar as well as sublime” can be considered quite an apt description for the Venus anadyomene scene; this is a symbol of love that has just as much of a sexual connotation as it does a romantic or emotional one. “The anadyomene speaks of Birth and Re-birth, of Generation and Re-generation, of Love and Triumph, of Purification and Salvation”[8] writes Heckscher, and these are all elements of the kind of love that became important to the art of the late 4th century.

The portrayal of love gradually moved away from subtle distinctions and grew instead into something truly grand which was expressed through this vessel of sex and beauty that was Venus herself. Love in art was no longer found through capturing simple human connection but instead was about representing iconography which communicates much larger ideals and expectations. Hellenistic art pushed the boundaries farther beyond past ideals and symbolism, as Hanfmann puts it in his paper on Hellenistic art:

Neither the cult image nor the mythological, biographical cycle are the most expressive vehicles of Hellenistic creativity. Its full grandeur and splendor revealed itself in divinely hallowed, sacral but not sacred, atmosphere of heroic myth, and, on a more comprehensive scale, in complexes which nature, architecture, sculpture (…) were united for the sake of the total effect in a new sense of an immediate nature-given reality.[9]

It is precisely this “new sense of an immediate nature-given reality” that breathes life into pieces such as Sleeping Hermaphrodite (Figure 4). This marble statue depicts Hermaphroditos, a son of Hermes and Aphrodite peacefully asleep on a plush mattress that was actually constructed by the Baroque sculptor Bernini centuries after the original form of Hermaphroditos was created. Hermaphroditos is said to be this perfect blend of feminine and masculine form, a perfect hermaphrodite and a word obviously built from the two parents Hermes and Aphrodite.

At first glance the statue seems undoubtedly feminine and, passing by it in the Louvre, you would never guess the reality off hand. There is an evident grace and fullness to the sleeping figure, soft lines and smooth curves, that produce a luxuriously feminine effect. The hair is long and flowing, curling around the temples before it is wrapped into a bun at the nape of the neck. Even the facial features drift somewhere in the greyness between masculinity and femininity: flawlessly smooth and with a definite lean towards idealization, like a child’s face on the brink of fully realized gender and existing instead in the in-between of their fresh youth. They seem deep in sleep, the pose of crossed arms as their pillow and knees slightly bent playing very naturally although the more you examine the body the more you realize how twistingly unrealistic for sleep the contortion might be. In this way the contrapposto position comes to mind, with its curving ‘S’ posture and precise middle ground between movement and standing still. The ‘S’ exists in this sleeping piece as well, even more obvious than we see with the jutting hip of the contrapposto. These curves accentuate and distract the viewer into the immediate assumption that we see are viewing a lovely, peaceful, young woman.

Everything about the posture and position of the body has been sculpted to conceal. At first the viewer cannot see whether the form has breasts as they lie on their chest or which sex exists in the space below their stomach as their legs are curved up towards them slightly. The statue has also been quite cleverly placed in the museum so that the body’s bent knees are facing towards the wall and it’s back to the viewers strolling down the hallway into the adjoining rooms. It is only by stopping and deliberately choosing to do a full circle around the piece that you arrive at a very different realization from whence you began, a realization that lies hidden and yet perfectly obvious between the sleeping form’s legs. Suddenly the piece becomes your own little secret for a few moments, as you watch the people who saunter past a lovely sleeping woman instead of pausing to uncover what you have found. This Hellenistic piece plays with the viewer, inviting you in to its own private, imaginary world while you circle the varying curves of marble. There is something private and hushed that exudes from it, and not only after you realize the hermaphroditic element. Unlike the other pieces that we have looked at today this one introduces the concept of voyeurism and therefore invites us, the viewer, to be a part of this statue’s narrative. We are given agency because this piece makes us aware that we are spectators. We are supposed to be gazing, we are supposed to think of how lovely the figure is and feel as if we could practically shake the figure awake.

What strikes the eye first in Sleeping Hermaphrodite is evidently how wonderfully asleep they are. Even their toes seem nonchalant and unaware, the left foot resting frozen somewhere in the midst of rubbing against their right calf absently. You can immediately feel the intimacy of this image. After all, what is more private, more trusting, than a sleeping and blissfully unaware being? All your shields and weapons must be put down when you are asleep, there are no more defensive lines that can protect you. Therefore, this vulnerable nude figure immediately becomes an indirect embodiment of love. The intimacy that the artist has captured here and the beauty of the figure elicits a clearly romantic note. This is taken to a new height when we remember that the character depicted, Hermaphrodite, is a child of Aphrodite. Consequently, this piece has another separate connotation with “love” before the actual scene even begins to stir any romantic notes within the viewing audience. This Hellenistic statue incorporates multiple concepts and perceptions of love. Yet this piece moves beyond that and into an incorporation of the viewer’s gaze. There is tenderness and intimacy in this piece, a side of love explored through the kourotrophoi of the Mycenaeans, but it is brought out in a much different way. We see the intimacy because we are a part of the scene. There is vulnerability in sleeping all alone and when you walk past Sleeping Hermaphrodite you can feel it because you are the one with the power. You are looking at them open and defenseless against you. There is also a sexual connotation, a passionate connotation and an iconography here because this is a naked, relaxed, beautiful character from mythology (and a child of Aphrodite). This piece is entrancing not merely because of a unique interpretation of love but because it invites the viewer to be affected and enthralled.

The ancient Greeeks knew that love was greater than one thing – compared to our stunted and limited English vocabulary, the Greeks had many different words. Their ancient words used éros for the sexual affection, and philía, for family or brotherly love. They had storgē for that motherly affection we can find even in Mycenaean pieces.[10] The Mycenaean terracotta of a woman and child shows us just this nurturing, quiet sort of storgē love. The Berlin painter’s vase shows us éros love through a series of well thought out sexual symbols, reminding us of a very different side to love. Vénus Anadyomène reminds us of some of the first iconography paired with the concept of love as well as the varying ideals that can fall under it while Sleeping Hermaphrodite takes all of these different interpretations and rolls them into one larger romantic form, even inviting the viewer to share in this experience of discovery in love. The human connection we experience in our own love can be found in ancient art, even in the small figurines of the Mycenaean period. By the time the Hellenistic period rolls around, ancient art has been steadily shifting its subject matter from simply displaying the iconography or history that often inhabits earlier styles, particularly in both archaic Greek and classical periods. Love is indeed a “many-spendored thing” and the varying images found throughout ancient art splendidly reflect these many aspects of Aphrodite’s kingdom.

Bibliography:

- Boardman, John. “The Phallos-Bird in Archaic and Classical Greek Art.” Revue Archéologique, no. 2. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1992, pg. 227–242. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41737544. Web.

- Clark Liassis, Nora. Aphrodite and Venus in Myth and Mimesis. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2015. eBook Collection (EBSCOhost). Web.

- Fountoulakis, Andreas. “The Artists of Aphrodite.” L’Antiquité Classique, vol. 69. 2000, pg. 133–147. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41660040. Web.

- Hamilton, Edith. Mythology. Boston: Little Brown, 1942.

- Hanfmann, George M. A.. “Hellenistic Art.” Dumbarton Oaks Papers, vol. 17. Washington DC: Dumbarton Oaks, 1963, pg. 77–94. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1291191. Web.

- Heckscher, W.S. “The ‘Anadyomene’ in the Mediaeval Tradition: (Pelagia – Cleopatra – Aphrodite) A Prelude to Botticelli’s ‘Birth of ‘Venus.’” Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek (NKJ) / Netherlands Yearbook for History of Art, vol. 7. BRILL, 1956, pg. 1–38. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/43872969. Web.

- Krznaric, Roman. How Should We Live?: Great Ideas from the Past for Everyday Life. New York: Bluebridge Press, 2013.

- Leach, Brenda Lynne. Looking and Listening : Conversations Between Modern Art and Music. Rowman and Littlefield, 2015. eBook Collection (EBSCOhost). Web.

- Lovatt, Helen. The Epic Gaze : Vision, Gender and Narrative in Ancient Epic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013. eBook Collection (EBSCOhost). Web.

End Notes

- Olsen, Barbara A. “Women, Children and the Family in the Late Aegean Bronze Age: Differences in Minoan and Mycenaean Constructions of Gender.” World Archaeology, vol. 29, no. 3. Abingdon: Taylor and Francis Ltd, 1998, pg. 384–387. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/125037. Web.

- “Search the Collection.” Louvre Museum | Paris, https://www.louvre.fr/en/moteur-de-recherche-oeuvres. 27 Nov. 2019.

- Thompson, Francis. “In No Strange Land,” in The Hound of Heaven and Other Poems. New York: Branden Books, 2014.

[1] Thompson, Francis. “In No Strange Land,” in The Hound of Heaven and Other Poems. New York: Branden Books, 2014. p. 31.

[2] Krznaric, Roman. How Should We Live?: Great Ideas from the Past for Everyday Life. New York: Bluebridge Press, 2013.

[3] Olsen, Barbara A. “Women, Children and the Family in the Late Aegean Bronze Age: Differences in Minoan and Mycenaean Constructions of Gender.” World Archaeology, vol. 29, no. 3, (1998), pg. 384.

[4] Krznaric, Roman. How Should We Live?: Great Ideas from the Past for Everyday Life. New York: Bluebridge Press, 2013.

[5] Boardman, John. “The Phallos-Bird in Archaic and Classical Greek Art.” Revue Archéologique, no. 2, (1992), pg. 227.

[6] Hamilton, Edith. Mythology. Boston: Little Brown, 1942. p. 33.

[7] Heckscher, W.S. “The ‘Anadyomene’ in the Mediaeval Tradition: (Pelagia – Cleopatra – Aphrodite) A Prelude to Botticelli’s ‘Birth of ‘Venus.’” Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek (NKJ) / Netherlands Yearbook for History of Art, vol. 7, (1956), pg. 3.

[8] Ibid. p. 3.

[9] Hanfmann, George M. A.. “Hellenistic Art.” Dumbarton Oaks Papers, vol. 17, (1963), pg. 83.

[10] Krznaric, Roman. How Should We Live?: Great Ideas from the Past for Everyday Life. New York: Bluebridge Press, 2013.